What Makes a Great Villain? Antagonist Archetypes in Movies

Nothing makes our hero more heroic than an equally horrific opponent, aka the villain.

The rival of the story, or the main antagonist, is the one who keeps it intriguing. However, the word “antagonist” is Greek in origin and refers to “the one who initiates change.”

The antagonists are the one initiating the plot. You can say, bad guys do things and good guys respond.

So, what does it takes to make an impactful villain?

While there’s no guaranteed recipe, we have isolated some characteristics that recur in the best movie villains of all time.

We’ll be breaking down 3 patterns for a villain. For each type, we’ll evaluate their defining characteristics and see how writers have tackled these villains previously. We’ll also look at some screenplays to see how these villains actually get written on the page.

Spoiler Warning: We’ll be spoiling the following movies:

- The Dark Knight

- Se7en

- There will be blood

Let’s begin with the first archetype of a villain.

The Mirror Villain

These villains are the exact opposite of the hero but also share certain traits, values, or methods. They are two sides of the same coin. This is Magneto to Professor X, Kylo Ren to Ray, and Voldemort to Harry Potter. Here’s K.M. Wyand’s definition.

“Mirror characters tend to share several qualities and are used to complement and highlight each other’s traits.”

Because of this unique and close relationship, mirror villains are best utilized when creating external conflict within the plot and internal conflict within the development of the hero himself.

For a fantastic example of a mirror villain, see “The Dark Knight” written by Jonathan and Christopher Nolan.

Assign Parallel Traits

The movie starts by assigning parallel traits to the hero and villain.

Both Batman and the Joker are relative outsiders to their own kind. The joker lays out this comparison on page 86, scene INT. Gotham Central – Night, when he says:

“To them, you’re just a freak. Like me.

They need you right now, but when they don’t…

they’ll cast you out, like a leper.”

Challenge the hero’s sense of purpose.

Next, lay out a path where the villain challenge hero’s sense of purpose. Do they challenge the hero’s worldview? Or sense of morality?

When Christopher Nolan spoke on the Joker’s mirror role to Heath Ledger. He spoke:

“He’s a very human monster… as the Joker does things in the story, it tests the characters, he forces them to confront things about themselves” ~ Christopher Nolan

The Joker forces Batman to break his one rule of no killing by making him choose between saving Harvey or saving Rachel.

Even after making him choose, being the mirror villain, the Joker knew he would pick Rachel, and tricked him to the wrong address. This sequence of events ultimately pushes Batman to question his very purpose.

The Joker also challenges Harvey Dent’s sense of morality in the hospital scene. Harvey succumbs to the Joker and becomes a villain of his own.

So, when writing a mirror villain remember to assign parallel traits and determine how the villain will challenge the hero’s sense of purpose.

The Looming Threat

Next up are the Villains that are more felt than seen. These are the villains whose threat is constant despite their limited presence in the story. And yet the danger they pose hangs oppressively over the hero.

Think of the Eye of Sauron, “The Zodiac Killer.” In some cases, we never see them at all. Like It in “It Follows“.

This villain archetype requires a lot of imagination from the audience. Which when done right can create an even more terrifying or imposing threat. A great example of a looming threat villain can be found in “Se7en” written by Andrew Kevin Walker. Let’s see how Walker builds a character that we almost never see.

Keep the Villain Absent

First and most obviously, the goal is to keep the villain absent as much as possible. In Walker’s script, John Doe makes two brief appearances before his grand reveal.

We see his first appearance on page 61, where Doe poses as a photographer.

“- Closed crime scene, get out. – I got a right to be here.

– UPI photographer. – Get out.

Get out. Jesus. – F*cking jerk. F*ck you.

I got your picture, man. – Oh, yeah?”

And on page 71, Mills and Somerset are ambushed after they discover his apartment. It’s not until page 103 that John Doe officially presents himself in the precinct house, saying:

“- You’re looking for me.”

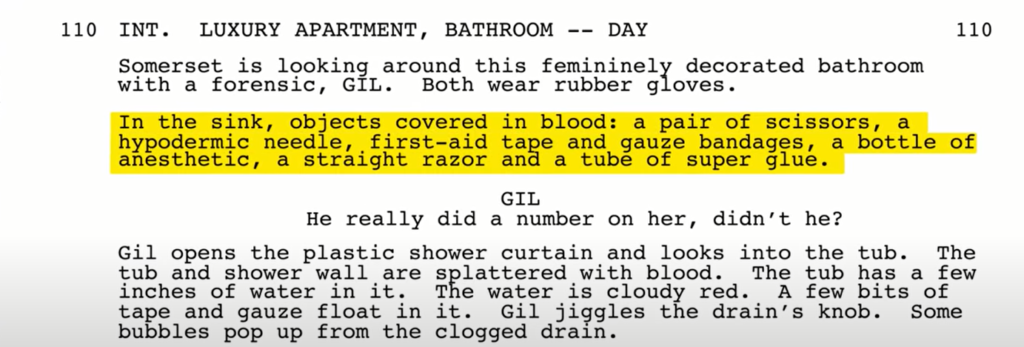

Out of 132 pages and an over two-hour movie, we’re only seeing John Doe for a very small fraction of the time. So, in order to keep him a looming threat from the beginning of the film, we need to focus on showing the aftermath.

Show the Aftermath of Villain’s Actions

Even though we don’t see the villain, we can witness what they are capable of. Here’s screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker on this approach.

“It was in the script that you didn’t see the things happen and that just seemed to me more horrifying to have to sit and imagine what it was like if you were forced at gunpoint to eat as much spaghetti as possible.” ~Andrew Kevin Walker

For all the horrific violence in “Se7en“, we see very little of it occur. This again activates our imaginations and makes us part of the storytelling.

For example, here’s how Walker describes the pride victims’ crime scene to paint a horrific scene in our mind.

Hear from Supporting Characters

The other way to sustain a looming threat is to hear from characters who have experienced the villain first hand. This way you continue to add to their villainous mythology while still relying on the audience’s imagination.

On page 94, we get this nightmarish eyewitness account. Just like Walker said, it can be more horrifying to not see these things happen.

Keep Motive Ambitious

The motivation behind these villains is usually ambiguous. Not knowing why these events are happening has two direct effects. One it creates anticipation from the audience to learn the truth. And two it helps maintain the villain’s power over the hero. Who is left struggling to understand.

On page 116, Mills and Somerset finally get some answers in their police car when Doe says:

“- I won’t deny my own personal desire…

to turn each sin against the sinner.”

In the final sequence, just like he has from the beginning John Doe has the upper hand. Mills is lured into Doe’s tangled web in a way he never expected.

So, remember one way to tackle writing a looming threat is to keep them absent as much as possible and build their mythology through their actions, first hand perspectives, and unclear or unknown motives.

Let’s move on to our final villain archetype.

The Villain Protagonist

This is simply a protagonist who exhibits villainous traits. They’re the quote-unquote hero but also the bad guy. These are characters like Alex in “A Clockwork Orange,” Patrick Bateman in “American Psycho,” and Tony Montana in “Scarface.“

In Paul Thomas Anderson’s “There Will Be Blood“, our villain protagonist is Daniel Plainview. An oilman whose ambition is so excessive it becomes his ultimate downfall. When creating any protagonist villain or otherwise they need certain elements including a goal, Antagonist, and Arc

Identify Goal, Antagonist, & Arc

Daniel pursues wealth and power until it eventually corrupts him completely

in a negative change called a fall arc. K.M. Weiland describes a fall arc as such.

“The protagonist in a fall arc will reject every chance for embracing the truth. And will fall more and more deeply into the morass of his own sins. His story will end in insanity, oppressive immorality or death.”

Balance Sympathy, & Villainy

Now with a character arc chosen, the most important consideration when tackling a villain protagonist is the balance between sympathy and villainy.

Villains are bad people who do bad things. But for a villain protagonist, they should possess some redemptive quality to keep the audience invested in their journey.

Here’s P.T. Anderson on his approach to writing Daniel’s character.

“- When I set out, I was trying to write a movie about fighting families. There’s brothers fighting but at the centre of it is this father and son.”

Plainview’s sympathy comes from his intense desire for family and his villainy is born out of his even stronger desire for wealth and power.

In the very first sequence, we witness Daniel solitary at pure ambition. He literally drags himself through the desert to cash in a bit of silver.

On page 6, an accident makes young H.W. an orphan. And Daniel takes him as his own. Which would be a purely selfless and admirable act if Daniel didn’t go on to use H.W. as a salesman’s prop.

“- I’m a family man.

I run a family business.

This is my son and my partner H.W. Plainview.

We offer you the bond of family

that very few oilmen can understand.”

Despite this exploitative relationship Daniel appears to genuinely care for his adopted son. He confides in him and mentors him in the oil business.

“- This is what we do.

And we don’t need the railroads and our shipping costs anymore.

You, see?

– Yeah.

– You see that?

– Yes.”

Then on page 57, Daniel gallantly rescues H.W. But he then leaves him to celebrate a marvel at riches that await him. This is a pivotal moment in Daniel’s character arc choosing business over family he takes a large step away from sympathy and towards villainy.

On page 79, Daniel sends him away to a school for the deaf. This abandonment plagues Daniel with insecurity and aggravates his violent impulses.

Now prior to all this with his adopted son on page 67 Daniel meets Henry. A long-lost brother he never knew he had. But after discovering him to be an imposter Daniel spirals further and becomes a murderer. And 20 years later at his lowest point rich and alone, Daniel goes off the rails completely.

Whatever sympathy he may have earned is dashed away in this final sequence with his son when he says:

“- You’re an orphan from a basket in the middle of the desert.

And I took you for no other reason than I needed a sweet face to buy land.

Did you get that?”

He also grows his murderous impulses which he now does without remorse.

As you write your own villain protagonist, remember to give them a complete character arc and to find a balance between sympathy and villainy.

The Finale

No matter which villain archetype you choose to write there are a few characteristics that are always important to focus on. And remember that this guide is just a jumping-off point. A villain might fit more than one archetype. Or defy expectations.

Sources:

Gladden, D. S. (2022, April 25). Villains and secondary characters: Mirroring effect. https://rio.tamiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1107&context=etds

Scriptwriting University. https://www.screenwritersuniversity.com/

Nolan, C., & Nolan, J. (n.d.). The Dark Knight [Screenplay]. https://www.nolanfans.com/screenplays/

Walker, A. K. (n.d.). Se7en [Screenplay]. https://www.scriptslug.com/scripts/medium/film

Anderson, P. T. (n.d.). There Will Be Blood [Screenplay]. https://www.hollywoodchicago.com/uploaded_images/therewillbeblood_script.pdf

2 Comments

[…] Heath Ledger, an Australian actor, is a renowned artist known for his intense dedication to craft. His filmography is a testament to his versatility, as he transitioned between diverse roles, from romantic leads to complex anti-heroes. […]

[…] are at the core of every great tale, in which villains play an equally pivotal role. Making a great villain goes beyond being simply caricatures of badness; their motives must go deeper than mere greed or […]